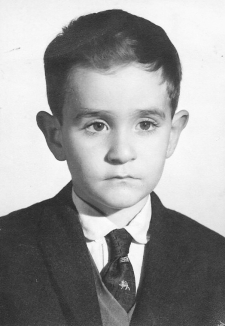

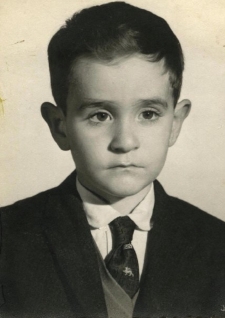

Now that I have posted so many pictures of family members when they were children, thereby violating their right to remain invisible figures, it is only fair that I post a photograph of my own younger self. Voilà. That’s me in Madrid in the very late autumn of 1963, the only child of Cuban refugees in the cold European capital ruled by Francisco Franco. A pinkish rubber stamp on the back reveals that the photograph was taken at the Estudio Fotográfico Peñalara, on calle Preciados, 17, whose telephone was 92 55 81. There is also a number that looks like a California zip code: 90647. My mother’s words are there too, a handwritten dedication to my maternal grandparents and great-grandmother back in Cuba: “Para mis abuelos y mi Bisa, con el cariño de Roberto Ignacio. Madrid, Dic. de 1963. A los tres años de edad.” I don’t known whether the picture was sent to the faraway island and recovered when my grandparents went into exile, or whether we kept it and took it with us to Puerto Rico, where we migrated to soon thereafter. The studio’s location on Preciados was not far from where lived, a pensión named La Montañesa on Plaza de la Marina Española. My mother recounts going with me to Galerías Preciados, the department store on that same street and now gone, and running into Sofía de Grecia, the future queen of Spain, who was there shopping for buttons. Sofía was pregnant, as my mother would soon be. What the princess needed buttons for remains a mystery.

Now that I have posted so many pictures of family members when they were children, thereby violating their right to remain invisible figures, it is only fair that I post a photograph of my own younger self. Voilà. That’s me in Madrid in the very late autumn of 1963, the only child of Cuban refugees in the cold European capital ruled by Francisco Franco. A pinkish rubber stamp on the back reveals that the photograph was taken at the Estudio Fotográfico Peñalara, on calle Preciados, 17, whose telephone was 92 55 81. There is also a number that looks like a California zip code: 90647. My mother’s words are there too, a handwritten dedication to my maternal grandparents and great-grandmother back in Cuba: “Para mis abuelos y mi Bisa, con el cariño de Roberto Ignacio. Madrid, Dic. de 1963. A los tres años de edad.” I don’t known whether the picture was sent to the faraway island and recovered when my grandparents went into exile, or whether we kept it and took it with us to Puerto Rico, where we migrated to soon thereafter. The studio’s location on Preciados was not far from where lived, a pensión named La Montañesa on Plaza de la Marina Española. My mother recounts going with me to Galerías Preciados, the department store on that same street and now gone, and running into Sofía de Grecia, the future queen of Spain, who was there shopping for buttons. Sofía was pregnant, as my mother would soon be. What the princess needed buttons for remains a mystery.

I don’t think I have any real memories from the few months we spent in Madrid, except perhaps two vague images that may or may not be actual recollections of the thing itself, but memories of stories I later heard. One concerns our first and only snowfall in the city. It suddenly began to snow — quite softly, as I recall — and my father and another man from Cuba living at our pension went outside to see what the strange powder from heaven was like. They made little snowballs and threw them at the window by which my mother and I were huddled. There are no pictures of any of that. The second memory is of an event that happened many times. It’s cold but there’s a bit of sun, and my father takes me to play in the gardens of the Palacio Real, just a few blocks from our pensión. I am only a little child, so my angle of vision is limited to the grass and the little white fences that divide the garden into smaller plots. Many years later, as a student working on a travel guidebook to Spain, I found myself on that spot, the Jardines de Sabatini, and the little white fences against the grass struck me as familiar objects I had seen before. When I later mentioned this to my father in Miami, he confirmed that, yes, in those few months when we were political refugees in Spain, he would take me every afternoon to play in the royal gardens. Time was regained, if only obliquely and vaguely. I’ve been told that I was mostly an unpleasant child, a veritable Prince-in-Exile who cried loudly and frequently. I disliked the food served in Madrid’s public dining halls for the poor, where we regularly had lunch. A true Cuban, I wanted black beans, but the workers at our dining hall regarded that as nourishment for pigs and told us so, serving garbanzos instead. On one occasion, my mother was served a huge piece of bone in her garbanzos; when she pointed that out, they told her, “Hoy le tocó hueso, señora.” I despised strangers and shut my eyes whenever someone said that I had beautiful eyes. I’m now sorry for my poor parents, who had to go everywhere with me and my crying self.

While in Madrid, my father could not have a job. Taking any kind of employment would have meant that we had decided to remain in Spain and trumped our efforts to secure entry into the United States. Therefore, my parents had little money but much free time in their hands. Every weekday morning my father would visit the very modern building of the U.S. Embassy on calle Serrano to inquire about the status of our Green Card application. He became acquainted with a foreign service employee who had also gone to a Jesuit school, a common life experience that supposedly helped expedite our case. I would be left in my mother’s care all day, a routine that revolved around her searching for a warm place to be. Like in some sad novel by Benito Pérez Galdós, our room in the pensión lacked any form of heat, which sent us out into the city to seek the shelter of well-heated spaces such as department stores and, almost daily, the Museo del Prado. If exile was a long gray cloud that hung over my parents, the Prado must have been my own early silver lining. As my mother recounts in a notebook where she records her memories of leaving Santiago de Cuba and surviving in Madrid, my favorite spot at the Prado was the room in which Las Meninas then hung. At the time, a mirror was placed in front of the painting. My favorite practice was to stand in front of the mirror, with the canvas behind me, and see myself as yet another minuscule figure in that melancholy realm of royals and servants and a sleeping dog. I can’t recall exactly what I saw, but I can imagine myself standing next to the Infanta Margarita, a girl only a few years older than me, a child as quiet and perhaps as unhappy as I must have been far from my grandmothers and great-grandaunt, my own old maids of honor now absent. In truth, I don’t have any real memories of those first visions of the strange canvas full of canvasses, but I have returned to Madrid many times — in fact, it’s the only city I’ve been to at least once in every decade of my life — and many times stood in front of the gray princess, my old playmate. To this day, in my university lectures, there is no subject I relish as much as Velázquez’s artifact of self-regard.

Which brings me to this blog. May I use this blog to reflect for a moment on what this blog is, or is about, or seeks to accomplish? This blog about discovering, mapping and possessing a series of spaces on both sides of the Atlantic: Madrid, for one; but also Barcelona, where some members of the family went to live; Newfoundland, where we spent a few desperate hours; Haiti, where some ancestors fled to and died, at least one of them violently; Philadelphia, the free city in which at least one of them, a young refugee, was married; New Orleans and New York, where some practiced honest crafts while at least one engaged in shameful trades; Puerto Rico, to which we arrived as exiles but where my brother and sister were both born. And it’s about France, of course, the birthplace of many of those ancestors, the land from which they migrated but also the idea, if not the actual place, to which they kept returning for decades. But first and foremost, I suppose, this blog is about reclaiming Cuba, a country to which I have no special desire to return, or even visit, but which I still think is mine. From time to time, I dream of Cuba. Just two nights ago I dreamed I went there without a passport. I sort of just walked in, like people do who cross the border into Tijuana. The landscape was full of royal palms, as if the battered republic had become a lush and endless repetition of its coat of arms. I suppose this particular dream came about because everyone seems to be going to Cuba these days. They can have that pretty island, but can they tell such stories about it as I can? In my dream, if I remember it correctly, people — virtual strangers all of them — knew who I was because they had read this blog.

This blog is also a time machine — a failed one, like they all are. It’s about excavating the past and trying to preserve it, which ultimately, pace Proust, can’t be done. It’s a museum of half-truths and yellowed images and defective, if unrelenting, storytelling. The old coffee and cacao plantation called La Reunión, where is it? The many ships that transported these folks back and forth across the Atlantic, aren’t they all sunken by now? The many letters and diaries penned in Cap-Français or Sitges or Bordeaux, can anyone read them? The past has passed. Consider this. Even if we eventually find out where Adolphe Vidaud du Dognon de Boischadaigne was born — either France or Cuba, a mystery that obsesses my genealogist cousins and me — what would that arduously acquired knowledge really mean? My own links with the ancient white-bearded man are tenuous at best. True, he was my second great-grandfather, but, if my arithmetic is correct, I have thirty-two of those; Adolphe, in turn, must have hundreds, if not thousands, of direct descendants by now. Whatever he was, I am not; or I am not only what he was; nor am I the only one who is some of what he was. Consider this too. Even if we reconstruct his biography profusely and delicately, the man is dead and won’t come back. I can write and you can read about him even as we stare into the looming absoluteness of non-consciousness. And even if those ties that link Adolphe Vidaud du Dognon de Boischadaigne with this Blogger may be twisted and turned into a string of words and images signifying something, what will they mean when we are all dead, when no one clicks on this link anymore, when the web itself collapses under the burden of its own infinite links?

This blog is also a time machine — a failed one, like they all are. It’s about excavating the past and trying to preserve it, which ultimately, pace Proust, can’t be done. It’s a museum of half-truths and yellowed images and defective, if unrelenting, storytelling. The old coffee and cacao plantation called La Reunión, where is it? The many ships that transported these folks back and forth across the Atlantic, aren’t they all sunken by now? The many letters and diaries penned in Cap-Français or Sitges or Bordeaux, can anyone read them? The past has passed. Consider this. Even if we eventually find out where Adolphe Vidaud du Dognon de Boischadaigne was born — either France or Cuba, a mystery that obsesses my genealogist cousins and me — what would that arduously acquired knowledge really mean? My own links with the ancient white-bearded man are tenuous at best. True, he was my second great-grandfather, but, if my arithmetic is correct, I have thirty-two of those; Adolphe, in turn, must have hundreds, if not thousands, of direct descendants by now. Whatever he was, I am not; or I am not only what he was; nor am I the only one who is some of what he was. Consider this too. Even if we reconstruct his biography profusely and delicately, the man is dead and won’t come back. I can write and you can read about him even as we stare into the looming absoluteness of non-consciousness. And even if those ties that link Adolphe Vidaud du Dognon de Boischadaigne with this Blogger may be twisted and turned into a string of words and images signifying something, what will they mean when we are all dead, when no one clicks on this link anymore, when the web itself collapses under the burden of its own infinite links?